A Ryanair Boeing 737-800, registration EI-DYD performing flight FR-4199 from Madrid,SP to Tenerife North,CI (Spain) with 182 passengers and 6 crew, was on final approach to Tenerife's runway 30.

A Binter Canarias Embraer ERJ-195-E2, registration EC-OEA performing flight NT-6062 from Tenerife North,CI to Madrid,SP (Spain) with 116 passengers and 5 crew, was cleared for takeoff from runway 30. In the moment the aircraft rotated for takeoff, tower cleared FR-4199 for landing on runway 30, the crew however elected to go around.

Spain's CIAIAC reported: "... a loss of separation occurred. The crew of the BOEING 737-800 aircraft was instructed to increase the climb rate and maintain an altitude of 5,000 ft and performed an airfield circuit north of the runway, subsequently landing normally. The EMBRAER 195 aircraft continued with the scheduled takeoff and continued the flight to Madrid Barajas Airport (LEMD). There was no personal or material damage." and opened an investigation into the occurrence.

On Oct 16th 2025 the CIAIAC released their final report concluding the probable causes of the incident were:

The investigation has determined that the loss of separation occurred as a result of a late takeoff clearance when there was another aircraft on final approach that had also been cleared to land, without sufficient minimum separation between the two aircraft.

It is considered a contributing factor that the controller who was acting as instructor was slow to realise that the controller receiving instruction was not able to handle the situation effectively enough.

The CIAIAC analysed:

The scenario we are faced with, which is very frequent nowadays, is that in the tower there was an instructor controller and a student controller, who was the one who was handling the communications of the positions, both local and taxiing, and the issuing of clearances. There was also a third controller in the unit, who was not involved in the incident, managing the approach control service.

The student controller had obtained his licence five (5) months earlier, but only had nineteen (19) days of on-the-job training, i.e. halfway through the period.

At the time of the incident, both the instructor and the trainee had been on duty for less than one (1) hour, so it does not appear that the working conditions were degraded by fatigue and had a direct influence on the incident.

Both were seated together, the instructor to the left of the student, in the local position, and the student to the right, although the student managed both positions, so the seating arrangement was not an added factor that could have influenced the instructor's decision to take command of the situation.

The student controller planned how to handle the aircraft he was managing, which consisted of first authorising the landing of the aircraft with call sign RSC59QC, which was not involved in the incident, then lining up the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z on the runway while the former was landing and taxiing on the runway to leave at exit E3, which is the usual exit for this type of aircraft, and once it had cleared the runway, authorising the taxiing aircraft to take off at the head of the runway.

He finally planned to authorise the landing of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW.

In accordance with the planning he had done, he instructed an aircraft with call sign RSC59QC to land on runway 30 and immediately afterwards instructed the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z to enter and align on the aforementioned runway, but with a conditional clearance, i.e. to do so once the previous aircraft had overtaken his position at the head of the runway.

What he did not do was to ask this second aircraft if it was ready for an immediate departure, when the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW was at 12.4 NM on long final and had the approach frequency (APP) tuned.

The instructor also failed to intervene to correct the situation. Such an intervention would have been a good preventive barrier.

When the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW first contacted the tower, they were informed by the instructor that there would be a departure (that of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z) before they landed. In this case, he did foresee the situation and anticipated events.

Another condition that influenced the loss of separation was that the aircraft with call sign RSC59QC could not leave the runway through the fast exit E3, as usual, because there was an aircraft starting to reverse to enter the take-off sequence and the instructor was forced to ask the crew of this aircraft to clear the runway through exit E2, which is at the end of the runway.

This change caused the aircraft to occupy the runway longer than planned and delayed the takeoff of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z, which at that time was starting to enter the runway. At the same instant the other aircraft RYR5LW was at 6.6 NM on final.

In this communication, the local student controller did not have the foresight to inform the aircraft that it had to leave the runway not to delay, as at that point it still had to cover another third of the runway. This warning was made in a second, later communication.

The Student controller informed the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW to wait for late clearance, when it was at 5.4 NM with a speed of 190 Kt (GS), while the aircraft IBB900Z was turning to line up with runway 30.

Subsequently, the student controller also attended to other aircraft, including the aircraft that had landed and left the runway (RSC59QC) to instruct it to proceed to a specific parking position, giving way to another aircraft of his company.

During this communication he was unaware that the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW was already on short final at only 2.8 NM from the threshold and with a speed of 190 kt (GS).

At that moment, the trainee authorised the take-off of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z and although he informed the crew of this aircraft that there was another aircraft on short final at 2.5 NM from the threshold, he did not ask them to make an "immediate" take-off.

The instructor could have intervened but did not realise that the situation had been compromised.

It could have been considered a preventive barrier to have taken some action to ensure separation.

When the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW then asked the tower if they were cleared to land, being 1.2 NM from the threshold with a speed of 160 kt, the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z had just started the take-off run.

The instructor also failed to react at the time and missed a second chance to realise that the situation was very unsafe and that some alternative measure should be taken immediately as a preventive barrier.

Instead, it was the trainee who responded by denying clearance to land because there was traffic on the runway.

This would indicate that the trainee was not able to vary his initial scheme and come up with an alternative that would ensure the loss of separation, such as asking the crew of the aircraft that was on short final to slow down.

The student gave clearance to land to the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW, when it was 0.1 NM from the threshold with a speed of 150 kt (GS) and the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z was still on takeoff run having passed exit E3, and with a speed of 130 kt (GS).

The fact that the instructor did not intervene and the fact that the trainee was not able to quickly find an alternative plan led to a failure to comply with both SERA.8005 b) 2) and 4.5.10.1 of the Air Traffic Regulations and the Operations Manual of the unit (5.2.2.1), by not maintaining the degree of separation established by these regulations between an aircraft taking off and an aircraft landing, resulting in the loss of separation between the two aircraft at that moment.

Specifically, this means that no aircraft shall be allowed to cross the runway threshold on final approach until the aircraft preceding it on take-off has crossed the runway end in use.

Nor was there any immediate recovery action by the controllers, since it was the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW who reported that they were aborting the landing without any response from the trainee or the instructor. It was even the crew who repeated the message again and required some kind of instruction to regain their balance.

Conflict resolution analysis

In an attempt to resolve the conflict, the student instructed the crew of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z to maintain an altitude of 5,000 ft when they reached it. However, this instruction was not effective as the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW, which had aborted the landing, remained above the one that had just taken off at all times.

As far as the recovery barriers were concerned, the instructor only took over communications when the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW alerted the tower that they had the other aircraft in close proximity and requested instructions to separate from it. At that time he instructed the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW to increase their rate of climb and the crew of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z to maintain their altitude.

The instructions he gave were effective because he got the two aircraft to separate, but he did not use standard phraseology. The specific phrase was "Yes, please, can you increase your rate of ascent". This was at 08:05:43 (07:05:43 UTC)

This fact, together with the delay in taking command and providing information contributed to the fact that both crews were not clearly aware of the situation they were in, with a minimum separation of 1.1 NM when they were at the same altitude, which occurred at 08:05:13 (07:05:13 UTC), i.e. 20 s before the instructor took over communications.

We can conclude that the instructor was overconfident in thinking that the trainee would be able to make the adjustment between the different aircraft efficiently, but the facts have shown that he should have intervened earlier to avoid the degradation of the safety margins and that the procedures of the control unit were not duly complied with, since the unit's Operating Manual clearly describes the parameters that must be evaluated and monitored when making an adjustment between an aircraft for immediate departure and another aircraft that is on arrival (the performance of both aircraft, their positions, the speed of the aircraft on final, the reaction time of the crew of the aircraft on the runway, etc.).

However, the provisions of the Information Circular of March 2024, which establishes a series of parameters to be taken into account by controllers when deciding whether to make an adjustment between an aircraft on take-off and another on arrival, were not taken into account either.

For this reason, during the investigation ENAIRE published an update of this circular in order to establish two preventive barriers. Firstly, not to authorise the take-off of an aircraft lined up on a runway that is 1:30 minutes from the threshold and secondly, if the aircraft that has not been authorised to takeoff has not yet started the run when the aircraft on approach is 1 minute or less from the threshold, it is recommended to cancel the take-off and instruct the other to go around (this is known as recovery action).

With regard to the management of the incident by the crews, the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z that took off had a runway speed of 60 kt (30.87 m/s) 33 seconds after the instructor began to transmit the take-off clearance, i.e. it had travelled 1,118.71 m, which means that it had only covered one third of the runway. This would indicate that they did not act quickly enough after receiving the instruction because they were not aware of the compromising situation they were in.

For its part, the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW maintained a speed of 200 kt when it was between 13.3 NM and 8.9 NM and 190 kt when it was between 8.9 NM and 3.2 NM, being aware that there would be a departure before landing.

This means that although they subsequently asked for instructions and aborted the approach, perhaps they could have increased the separation by reducing the speed more than they did.

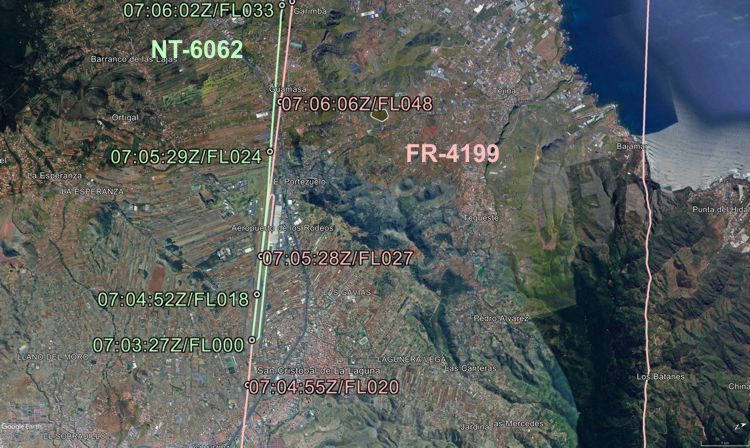

Map and trajectories (Graphics: AVH/Google Earth):

A Binter Canarias Embraer ERJ-195-E2, registration EC-OEA performing flight NT-6062 from Tenerife North,CI to Madrid,SP (Spain) with 116 passengers and 5 crew, was cleared for takeoff from runway 30. In the moment the aircraft rotated for takeoff, tower cleared FR-4199 for landing on runway 30, the crew however elected to go around.

Spain's CIAIAC reported: "... a loss of separation occurred. The crew of the BOEING 737-800 aircraft was instructed to increase the climb rate and maintain an altitude of 5,000 ft and performed an airfield circuit north of the runway, subsequently landing normally. The EMBRAER 195 aircraft continued with the scheduled takeoff and continued the flight to Madrid Barajas Airport (LEMD). There was no personal or material damage." and opened an investigation into the occurrence.

On Oct 16th 2025 the CIAIAC released their final report concluding the probable causes of the incident were:

The investigation has determined that the loss of separation occurred as a result of a late takeoff clearance when there was another aircraft on final approach that had also been cleared to land, without sufficient minimum separation between the two aircraft.

It is considered a contributing factor that the controller who was acting as instructor was slow to realise that the controller receiving instruction was not able to handle the situation effectively enough.

The CIAIAC analysed:

The scenario we are faced with, which is very frequent nowadays, is that in the tower there was an instructor controller and a student controller, who was the one who was handling the communications of the positions, both local and taxiing, and the issuing of clearances. There was also a third controller in the unit, who was not involved in the incident, managing the approach control service.

The student controller had obtained his licence five (5) months earlier, but only had nineteen (19) days of on-the-job training, i.e. halfway through the period.

At the time of the incident, both the instructor and the trainee had been on duty for less than one (1) hour, so it does not appear that the working conditions were degraded by fatigue and had a direct influence on the incident.

Both were seated together, the instructor to the left of the student, in the local position, and the student to the right, although the student managed both positions, so the seating arrangement was not an added factor that could have influenced the instructor's decision to take command of the situation.

The student controller planned how to handle the aircraft he was managing, which consisted of first authorising the landing of the aircraft with call sign RSC59QC, which was not involved in the incident, then lining up the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z on the runway while the former was landing and taxiing on the runway to leave at exit E3, which is the usual exit for this type of aircraft, and once it had cleared the runway, authorising the taxiing aircraft to take off at the head of the runway.

He finally planned to authorise the landing of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW.

In accordance with the planning he had done, he instructed an aircraft with call sign RSC59QC to land on runway 30 and immediately afterwards instructed the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z to enter and align on the aforementioned runway, but with a conditional clearance, i.e. to do so once the previous aircraft had overtaken his position at the head of the runway.

What he did not do was to ask this second aircraft if it was ready for an immediate departure, when the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW was at 12.4 NM on long final and had the approach frequency (APP) tuned.

The instructor also failed to intervene to correct the situation. Such an intervention would have been a good preventive barrier.

When the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW first contacted the tower, they were informed by the instructor that there would be a departure (that of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z) before they landed. In this case, he did foresee the situation and anticipated events.

Another condition that influenced the loss of separation was that the aircraft with call sign RSC59QC could not leave the runway through the fast exit E3, as usual, because there was an aircraft starting to reverse to enter the take-off sequence and the instructor was forced to ask the crew of this aircraft to clear the runway through exit E2, which is at the end of the runway.

This change caused the aircraft to occupy the runway longer than planned and delayed the takeoff of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z, which at that time was starting to enter the runway. At the same instant the other aircraft RYR5LW was at 6.6 NM on final.

In this communication, the local student controller did not have the foresight to inform the aircraft that it had to leave the runway not to delay, as at that point it still had to cover another third of the runway. This warning was made in a second, later communication.

The Student controller informed the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW to wait for late clearance, when it was at 5.4 NM with a speed of 190 Kt (GS), while the aircraft IBB900Z was turning to line up with runway 30.

Subsequently, the student controller also attended to other aircraft, including the aircraft that had landed and left the runway (RSC59QC) to instruct it to proceed to a specific parking position, giving way to another aircraft of his company.

During this communication he was unaware that the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW was already on short final at only 2.8 NM from the threshold and with a speed of 190 kt (GS).

At that moment, the trainee authorised the take-off of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z and although he informed the crew of this aircraft that there was another aircraft on short final at 2.5 NM from the threshold, he did not ask them to make an "immediate" take-off.

The instructor could have intervened but did not realise that the situation had been compromised.

It could have been considered a preventive barrier to have taken some action to ensure separation.

When the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW then asked the tower if they were cleared to land, being 1.2 NM from the threshold with a speed of 160 kt, the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z had just started the take-off run.

The instructor also failed to react at the time and missed a second chance to realise that the situation was very unsafe and that some alternative measure should be taken immediately as a preventive barrier.

Instead, it was the trainee who responded by denying clearance to land because there was traffic on the runway.

This would indicate that the trainee was not able to vary his initial scheme and come up with an alternative that would ensure the loss of separation, such as asking the crew of the aircraft that was on short final to slow down.

The student gave clearance to land to the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW, when it was 0.1 NM from the threshold with a speed of 150 kt (GS) and the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z was still on takeoff run having passed exit E3, and with a speed of 130 kt (GS).

The fact that the instructor did not intervene and the fact that the trainee was not able to quickly find an alternative plan led to a failure to comply with both SERA.8005 b) 2) and 4.5.10.1 of the Air Traffic Regulations and the Operations Manual of the unit (5.2.2.1), by not maintaining the degree of separation established by these regulations between an aircraft taking off and an aircraft landing, resulting in the loss of separation between the two aircraft at that moment.

Specifically, this means that no aircraft shall be allowed to cross the runway threshold on final approach until the aircraft preceding it on take-off has crossed the runway end in use.

Nor was there any immediate recovery action by the controllers, since it was the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW who reported that they were aborting the landing without any response from the trainee or the instructor. It was even the crew who repeated the message again and required some kind of instruction to regain their balance.

Conflict resolution analysis

In an attempt to resolve the conflict, the student instructed the crew of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z to maintain an altitude of 5,000 ft when they reached it. However, this instruction was not effective as the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW, which had aborted the landing, remained above the one that had just taken off at all times.

As far as the recovery barriers were concerned, the instructor only took over communications when the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW alerted the tower that they had the other aircraft in close proximity and requested instructions to separate from it. At that time he instructed the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW to increase their rate of climb and the crew of the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z to maintain their altitude.

The instructions he gave were effective because he got the two aircraft to separate, but he did not use standard phraseology. The specific phrase was "Yes, please, can you increase your rate of ascent". This was at 08:05:43 (07:05:43 UTC)

This fact, together with the delay in taking command and providing information contributed to the fact that both crews were not clearly aware of the situation they were in, with a minimum separation of 1.1 NM when they were at the same altitude, which occurred at 08:05:13 (07:05:13 UTC), i.e. 20 s before the instructor took over communications.

We can conclude that the instructor was overconfident in thinking that the trainee would be able to make the adjustment between the different aircraft efficiently, but the facts have shown that he should have intervened earlier to avoid the degradation of the safety margins and that the procedures of the control unit were not duly complied with, since the unit's Operating Manual clearly describes the parameters that must be evaluated and monitored when making an adjustment between an aircraft for immediate departure and another aircraft that is on arrival (the performance of both aircraft, their positions, the speed of the aircraft on final, the reaction time of the crew of the aircraft on the runway, etc.).

However, the provisions of the Information Circular of March 2024, which establishes a series of parameters to be taken into account by controllers when deciding whether to make an adjustment between an aircraft on take-off and another on arrival, were not taken into account either.

For this reason, during the investigation ENAIRE published an update of this circular in order to establish two preventive barriers. Firstly, not to authorise the take-off of an aircraft lined up on a runway that is 1:30 minutes from the threshold and secondly, if the aircraft that has not been authorised to takeoff has not yet started the run when the aircraft on approach is 1 minute or less from the threshold, it is recommended to cancel the take-off and instruct the other to go around (this is known as recovery action).

With regard to the management of the incident by the crews, the aircraft with call sign IBB900Z that took off had a runway speed of 60 kt (30.87 m/s) 33 seconds after the instructor began to transmit the take-off clearance, i.e. it had travelled 1,118.71 m, which means that it had only covered one third of the runway. This would indicate that they did not act quickly enough after receiving the instruction because they were not aware of the compromising situation they were in.

For its part, the crew of the aircraft with call sign RYR5LW maintained a speed of 200 kt when it was between 13.3 NM and 8.9 NM and 190 kt when it was between 8.9 NM and 3.2 NM, being aware that there would be a departure before landing.

This means that although they subsequently asked for instructions and aborted the approach, perhaps they could have increased the separation by reducing the speed more than they did.

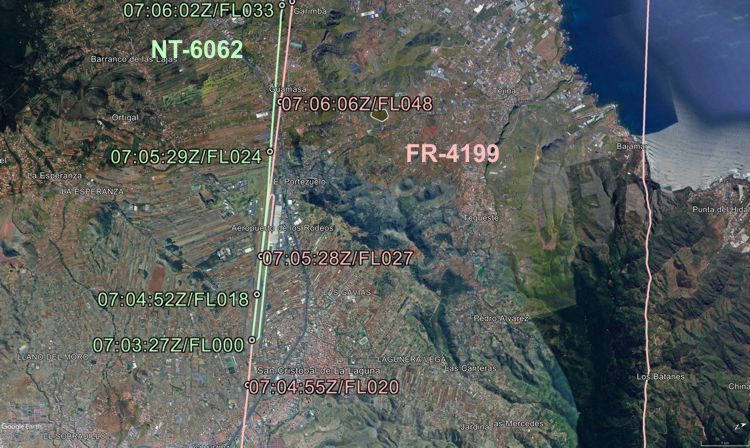

Map and trajectories (Graphics: AVH/Google Earth):

This article is published under license. Article Source

Published Date